Paul Troubetzkoy was born in 1866 at Intra, on the shores of the Lake Maggiore in Italy, about sixty miles from Milan. His father was a Russian prince who had married American opera singer Ada Winans and settled in Italy. So the colourful world of Italian opera – centred on La Scala, made a strong impression on him from an early age.

A bust of the legendary Russian opera singer, Fedor Chaliapin was modelled around 1898-1900 during Troubetzkoy’s visit to Russia. The sculptor was introduced to Chaliapin, then a young promising singer, by Savva Mamontov, a wealthy industrialist, art patron and a passionate theatre supporter. In a letter to the artist I.E. Bondarenko, Ilia Repin noted that Troubetskoy enjoyed listening to the singer and immediately started working on the bust: Troubetzkoy made two busts: one in painted plaster and the other in bronze’ (undated letter).

Troubetzkoy’s 1897 bronze portrait of Adelaide Aurnheimer (Fig 2) also known as Dopo il Ballo (After the Ball), is one of many which defines him as the ‘Singer Sergent of Sculpture’. She is dressed as the eponymous tragic heroine from Giacomo Puccini’s opera Manon Lescaut, premiered previously at the Teatro Regio in Turin.

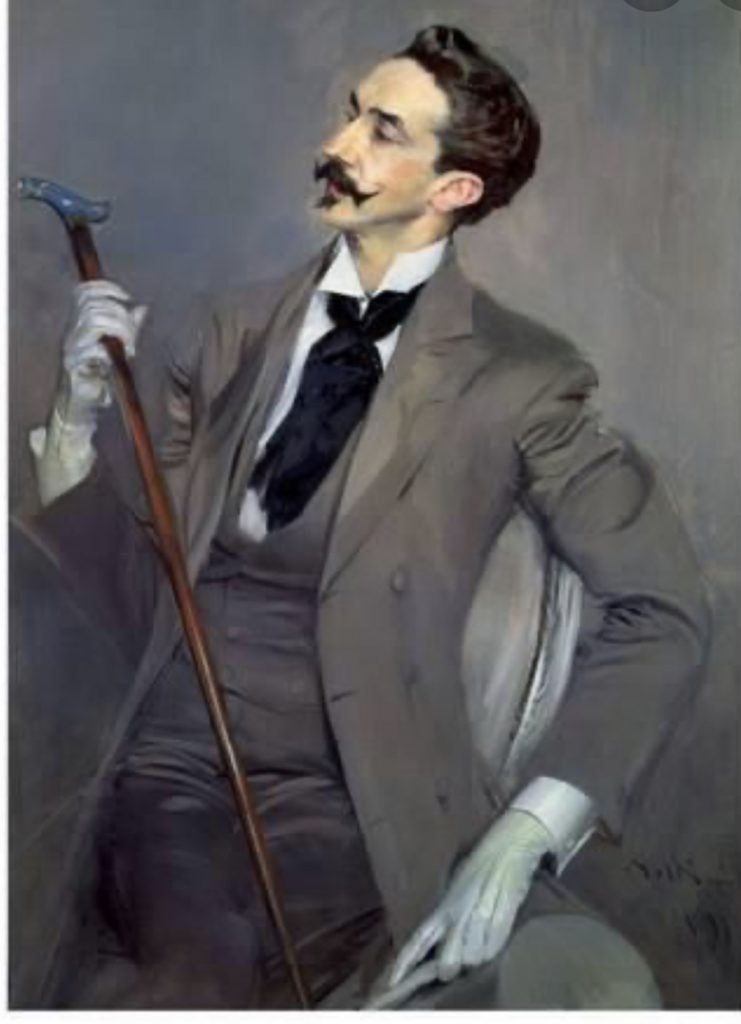

The fluidity of Troubetzkoy’s modelling technique suggests a portrait painter’s approach to sculptural form as he dabs clay with an impressionist’s touch which has encouraged comparisons with his contemporaries. Giovanni Boldini’s portrait of Lady Gertrude Campbell in the National Portrait Gallery, London (Fig 3) is one example; it evokes the elegance of the period and draws the viewer into the narrative, as if Lady Campbell had just glided onto a banquette at a grand ball. A similar example is John Singer Sargent’s portrait of Lady Agnew of Lochnaw in the National Gallery of Scotland (Fig 4). In each case their long ball gowns create undulating forms that cascade from the bodies of the sitters. Such comparisons position Troubetzkoy as the pre-eminent sculptor of the fin-de-siècle high society.

The three great figures in early 20th Century opera, Puccini, Caruso and Toscanini, were all modelled by Troubetzkoy in 1912.

When Troubetzkoy first arrived in Milan in 1884, Giacomo Puccini’s first opera was being staged. Puccini and Troubetzkoy became friends and were both influenced by other poets, writers, musicians and artists who were part of the so-called ‘Scapigliati’.

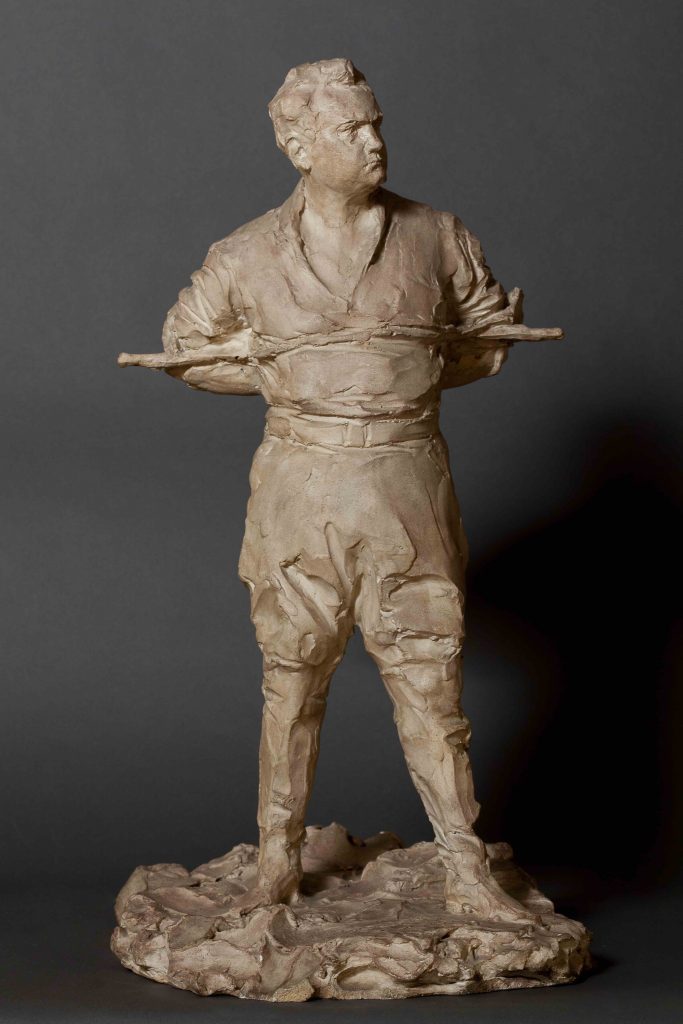

In the grounds of the villa at Torre del Lago where Giacomo Puccini spent the last 30 years of his life, on the shores of Lake Massaciuccoli, a lifesize statue of the composer smoking a cigarette, dominates the landscape. It is one of Troubetzkoy’s most iconic works. This was long before the link between smoking and cancer was identified. Sadly, Puccini died of complications of laryngeal cancer at only sixty-five.

The 1924 statue was based on Troubetzkoy’s 1912 cast of Puccini. Luigi Troubetzkoy recalls in his memoirs that he was called to the opera house by Toscanini who instructed him to send a telegram to his brother Paul to arrange a meeting to discuss the commission.

The sculptor depicted the legendary tenor Enrico Caruso in stage costume as Dick Johnson alias Ramerres in the Puccini opera “La fanciulla del West” (The Girl of the West). No doubt, he was inspired by photographs such as the one below taken during the performance.

In this role, Caruso fully transitioned from verismo’s Sicilian peasant to a working-class rebel in the American mould. Puccini wrote to Caruso on 13 January 1911: “Tell me how Fanciulla is doing, if the crowds are flocking to it and if it is paying me well [..]. I salute you, O singer of many notes, and hope that the cheek of a fanciulla [girl] will lie on your breast […] A kiss to my Rodolfo [of La Bohème] and my extraordinary Johnson from him who wishes you well.”

The opera premiered on December 10, 1910 at the Metropolitan Opera Theater, New York. It was the first world premier the Met had mounted. They spared no expense in turning the premier into a glittering social occasion, giving ‘exclusive’ advance interviews with conductor Toscanini and composer Puccini. Tickets were sold for twice their normal price, and on the black market some seats sold for $150 – an astronomical sum in 1910. After the final aria ‘Addio, California’ there were no fewer than fifty-five curtain calls.

As depicted in Edith Wharton’s novel The Custom of the Country, the Met was THE place to be seen -and even to snare a husband. Listening to music took a back seat to social climbing. Little wonder then that the great socialite Paul Troubetzkoy chose this location and this performance for his bronze of Caruso. The tenor, the composer and the sculptor were all at the height of their powers in 1910.