Paul Troubetzkoy was often described as an Impressionist sculptor by contemporary critics. He created effects similar to what the Scapigliati painters did on canvas by interweaving between his subject and the atmosphere around it.

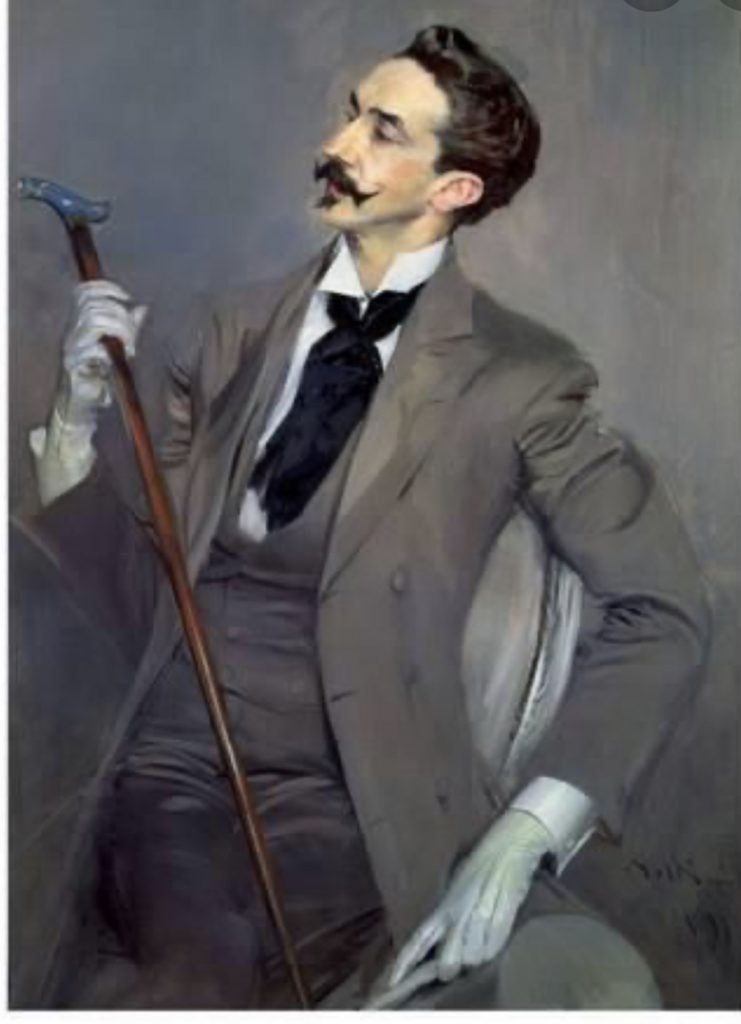

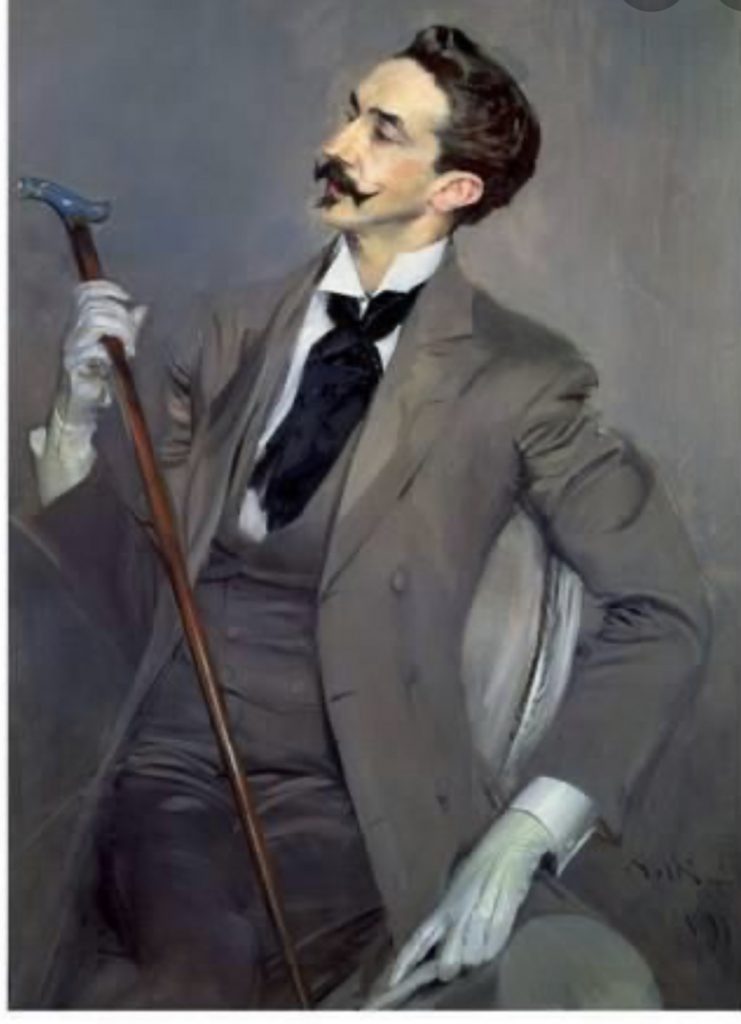

Troubetzkoy approached his portrait busts without using preparatory sketches of models. His working methods and aesthetic preferences produced bronze busts that showed evidence of their process of creation, with some lesser worked areas along with highly finished areas. In that sense he belongs to the Cosmopolitan Realist movement which encompassed John Singer Sargent, Giovanni Boldini and others (1).

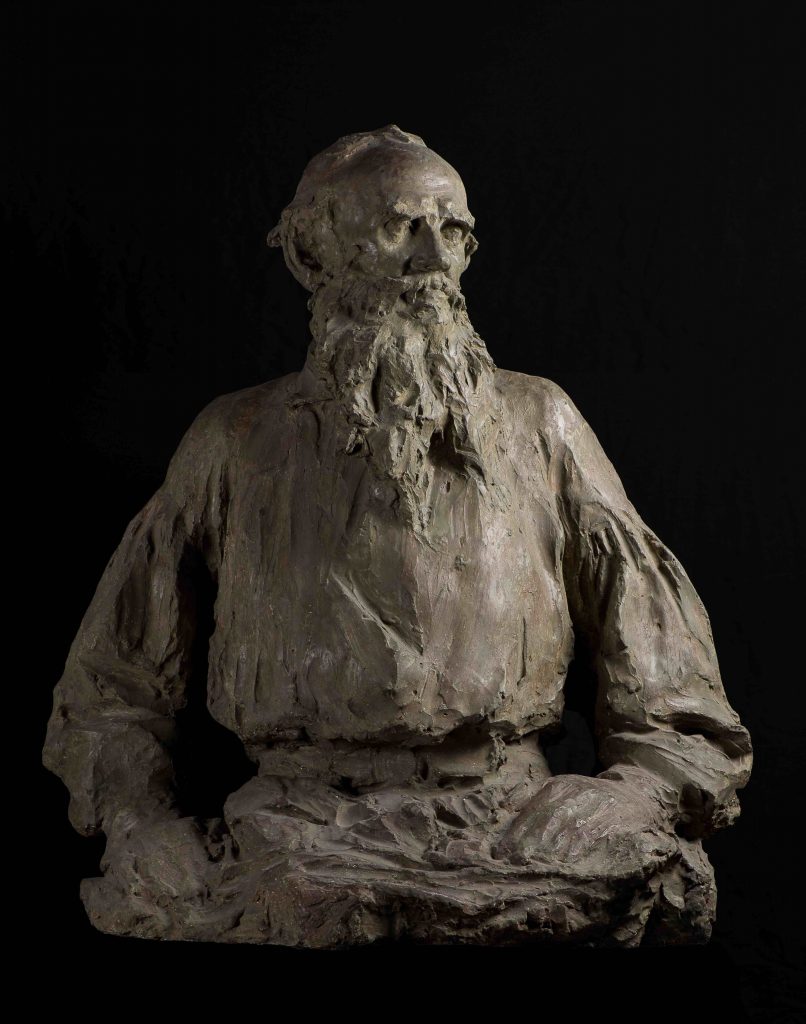

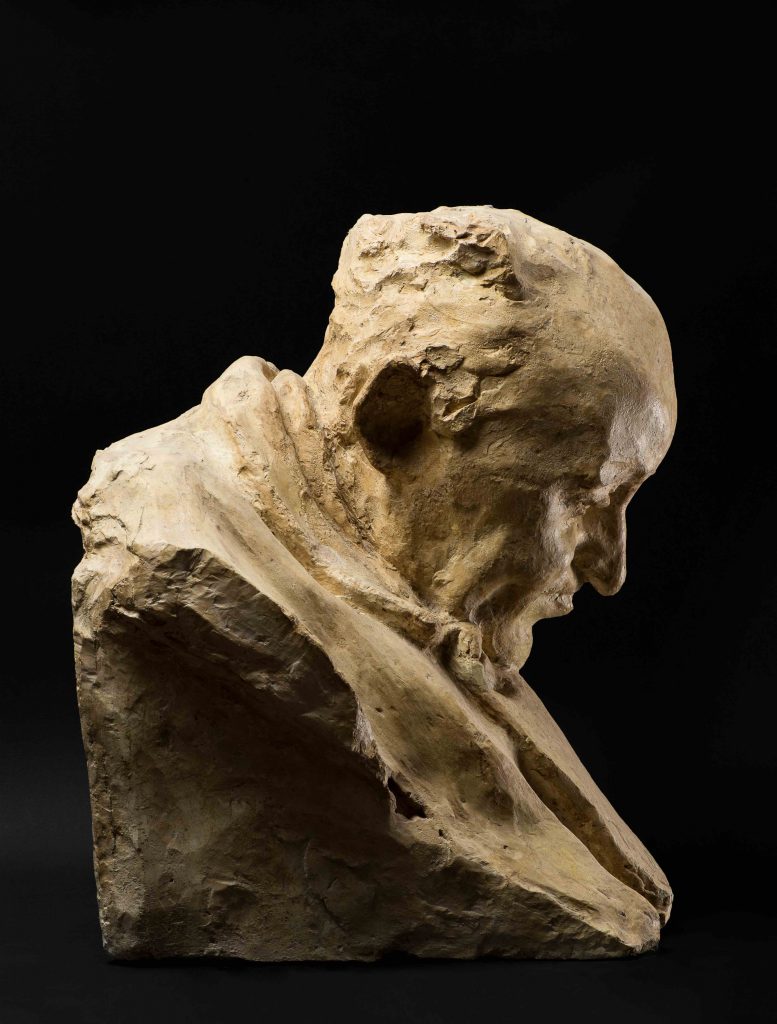

Troubetzkoy’s sculptural vision was clearly articulated in his bust of Leo Tolstoy. Tolstoy’s secretary wrote that the sculptor’s interest in the writer was not literary: he had never read any of his works. It was that Tolstoy had “a wonderfully sculpted head”. His modeling was guided by his imagination and his sense of form; he predicted the evolution of form in space and the way it moved. Part of this came from an understanding of nature, with the form growing from the inside, gaining strength and eventually opening up. His genius lay in his ability to grasp sketchy movements in his plasters.

John Singer Sargent was the portrait artist who closely resembled his contemporary Troubetzkoy in his use of elongation of his subjects to depict glamour. Andy Warhol commented that Sargent “made everybody look glamorous. Taller. Thinner. But they all have mood; every one of them has a different mood.” (2)

This 1881 sketch of his friend Vernon Lee from the Tate is an example of Sargent’s impressionist style; it was done in a single sitting which lasted only three hours. The free brush work adds ambiguity to a woman who “toyed with gender and stereotypes in a patriarchal world”. (3)

Sargent was able to work for only a few minutes in early evenings when the light was exactly right. He placed his easel and paints beforehand, and posed his models in anticipation of the few moments when he could paint the mauvish light of dusk. His friend Edmund Gosse recorded Sargent’s working method: “Instantly, he took up his place at a distance from the canvas, and at a certain notation of the light ran forward over the lawn with the action of a wag-tail, planting at the same time, rapid dabs of paint on the picture, and then retiring again, only, with equal suddenness, to repeat the wag-tail action. All this occupied but two or three minutes, the light rapidly declining, and then, while he left the young ladies to remove his machinery[…]” (4)

One of Troubetzkoy’s best known works is his bust of GB Shaw was created in Sargent’s London studio. Shaw records that “he worked convulsively, giving birth to the thing in agonies, hurling lumps of clay about with groans, and making strange, dumb movements with his tongue, like a wordless prophet. He covered himself with plaster. He covered me with plaster. And, finally, he covered the block he was working on with plaster to such purpose that, at the end of the second sitting, lo! there stood Sargent’s studio in ruins, buried like Pompeii under the scoriae of a volcano, and in the midst a spirited bust of one of my reputations, a little idealized (quite the gentleman in fact) but recognisable a mile off as the sardonic author of Man and Superman […]” (5)

The label ‘Impressionism’ in sculpture came from an approximate reconstruction of the Impressionist painters’ Salons. Although the Salons were intended to be interdisciplinary, only seven works categorised as sculpture were included across all eight editions (6).

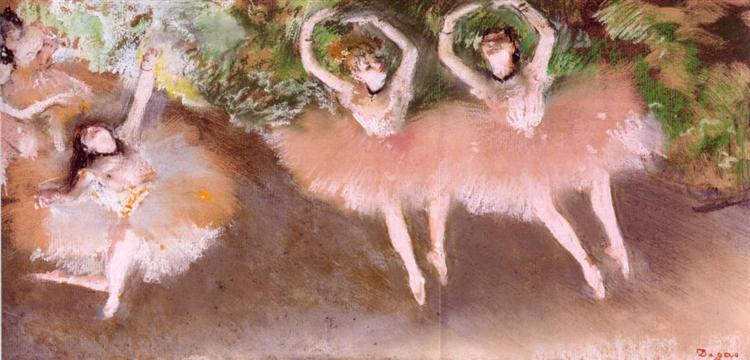

The first recorded reference to ‘impressionist sculpture’ came from the critic Jules Claretie. “Good God! We are going to see Impressionist sculptors!” he exclaimed after seeing Degas’s Little Dancer Aged Fourteen at the Impressionists’ sixth Salon des Indépendants in 1881. The work disturbed audiences with the realism of its tutu, ribbon and human hair, and Claretie saw it as a rejection of tradition, adding sarcastically that ‘they are starting to affirm their independence in the form of sculpture; colour was not enough’. This could be said to be the first Impressionist sculpture: it was a modern subject, with the artist deploying modern materials; the finish was rougher than usual; it was realistic rather than idealised in its depiction of the young dancer (7).

Degas’ impressionism style is vividly represented in his racehorses, which were experimental studies for commercial compositions. In one of these studies, the distortion of the horse’s head suggests its body flashing in and out of focus as it passes the eye.

In a context where artists explored new avenues to depict movement in sculpture, it was inevitable that Troubetzkoy was heavily influenced by Degas in his modelling of dancers, such as Countess Thamara Swirskaya in about 1909. She was then a renowned pianist and dancer who performed around the world (8).

The bravura technique which Troubetzkoy brought to bronze captures the dynamism and spirit of Thamara Swirskaya. He sought to improve the surface’s naturalism, investing his works with a unique crispness and sharpness. The Getty museum has a fine example, which reveals Troubetzkoy’s mastery of technique in the accurate but swift strokes of the modelling, showing his sensitivity to the subject.

Slowly, the boundaries between shapes start falling apart, what really matters is the eye’s impression and no longer the quality of the form. What is perceived is the continuity of the figure in the space.

The critic Edmond Claris wrote an essay on the subject entitled De L’Impressionnisme en sculpture in 1902. After Degas, the focus shifted to the work of Medardo Rosso, Rodin and his partner Camille Claudel. For example in Claudel’s Waltz (1889–1905) we see the sweep of the female partner’s dress both anchoring and conveying motion.

By the summer of 1886 a new name was added to the Impressionist group: Italian sculptor, Medardo Rosso, who exhibited his work at the Paris Salon. In the absence of public access to Degas’s sculptures, with the exception of one work, Rosso became the Impressionist sculptor par excellence, even though he never exhibited with the Impressionists themselves. One innovation was in the use of wax as a finished medium. Wax was frequently used in the modelling and casting processes, but it had been considered too fragile to be a permanent medium. Rosso cast a coloured wax outer layer around a plaster core. He was a friend of Eugène Carrière, who worked in a tenebrist style. Carrière was later a neighbour of Bourdelle, and in regular communication with Auguste Rodin. Rosso developed a rivalry with Rodin; as Rodin’s fame increased, Rosso displayed his insecurity by accusing him of stealing his ideas.

Rosso’s rather sparse output was confined to about fifty original works in twenty years. For the last 20 years he made no original work, only casting recasting some earlier works. He achieved some acclaim in the early 1900’s but once Cubism took hold in 1910, Rosso’s was eclipsed. His use of coloured wax to mimic qualities of stone, wood and flesh adds vibrance to his works. He is firmly in the Impressionist camp because his subjects are taken from his everyday life. Moreover, his surfaces imitate the effect of shadows and movement, as in his veils. Finally the patina is deliberately rough, making him an iconoclast among his peers. Only at close range do his casts reveal their figurative forms. Impressionist paintings are the direct opposite: they appear realistic from a distance and become rather abstract at close range (9).

Troubetzkoy was strongly influenced by the art of Medardo Rosso, in particular, by Rosso’s alternation of smooth and broken strokes on the surface of the sculpture and his “rough modeling”. Unlike Rosso, who aspired to “make himself forget about matter”, Troubetzkoy always maintained a balance between the basic elements of a sculpture and the space around them. The surface of his sculptures acquired an individuality: the “rough” strokes became more elegant and cultured.

It was Rodin who first discovered the potential of the Impressionist form. An important feature of this form is that “when presented only through its characteristic points, it stronger stirs up the imagination and creative mind of the beholder” (Vladimir Domogatsky). Relying on the eye’s tendency to resent the absence (or deformation) of a proper form in its proper place, the viewer would reinstate the natural form in his imagination.

Rodin is often seen in connection with the older sculptor Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, collaborator Camille Claudel or viewed as a founder of Modernist sculptor – particularly in the light of his sawing up of plaster casts of his pieces. So realistic was the early Age of Bronze figure (1875-7) that Rodin was accused of passing off a life-cast as a modelled sculpture – a very modern tactic, but one which Rodin vigorously disputed. Rodin’s work sometimes remained unfinished, which gave it an affinity with Impressionist practice. The case for Rodin as an Impressionist is more tangential than with the others. Rodin’s radical approach to the Burghers of Calais (1884-9) was compared to that of Monet, whom he exhibited beside once in 1889 (10).

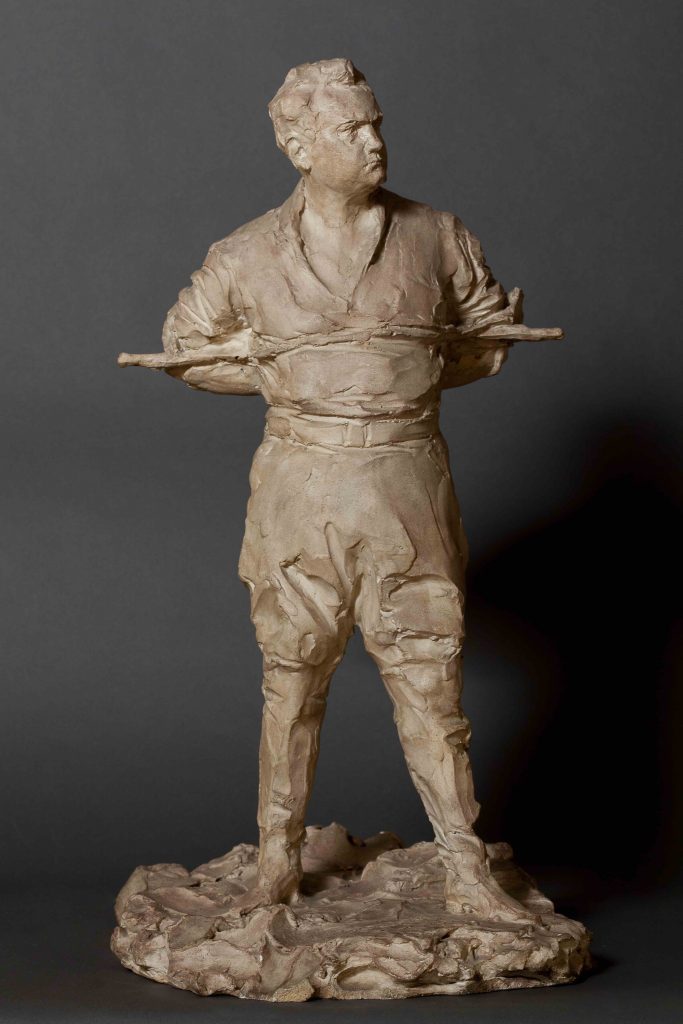

Troubetzkoy first met his fellow sculptor Auguste Rodin in the winter of 1905, when they worked together. The two men became friends, and it was around this time that Troubetzkoy conceived of his sculpted portrait of Rodin. Rodin stands with his hands in his trouser pockets, his left leg slightly forward, looking ahead (see image at the start of this article). The base of the statue is roughly modelled and irregular in shape. The figure leans against a supporting stump to waist height, also roughly modelled.

Rodin’s discovery of the method of enhancing form and emphasizing its characteristics had a limitless potential, and Rodin himself, very soon after the discovery, took the form to new heights – the pinnacle coming in 1900 at the World Fair in Paris. This innovative approach determined the aesthetics and artistic language of the early 20th century.

The sculptures above show how Rodin’s interpretation of shapes and form was also adopted by Troubetzkoy. Both sculptures have as a base an irregular and roughly modelled shape, enhancing the visual impression of “the moment”, as well as having their female figures emerge from the ground.

While Rodin’s style is characterized by a particular emphasis on emotion and expressiveness, Troubetzkoy demonstrates how his artistic output, even if influenced by Rodin at times, was “immune to external influences” (6).

Troubetzkoy’s elongated and elegant figures demonstrates his gradual development towards a more neutral style, particularly suitable for an international society portraitist. Troubetzkoy had been one of the very few able to apply the principles of impressionist sculpture to an aristocratic and more commercial context.

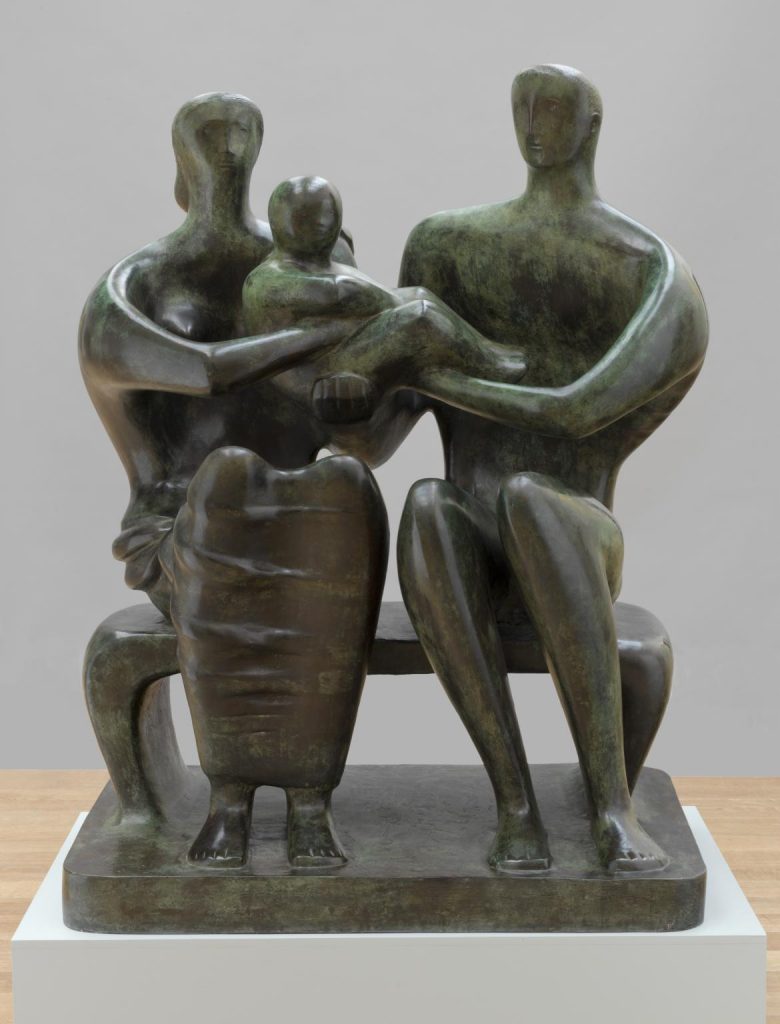

The lifespan of sculptural Impressionism was actually around a third of the lifespan of Impressionism in painting, because sculptors picked up the trend much later than painters. Rodin, Maillol, Bourdelle and Bernard developed and elaborated the Impressionist form. They were followed by Archipenko, Zadkine, Lipchitz, Moore and other avant-garde artists. They might for example use convexities in places diametrically opposite to where they should be in real-life objects, or holes within sculpted objects — are. Objects whose forms were modeled by the artist’s mind were becoming ubiquitous (11).

Inspired by different shapes and natural objects, Henry Moore’s works testify the transition from impressionism towards a new and abstract aesthetic, breaking traditional art standards.

A noteworthy character in the Impressionist environment was Rembrandt Bugatti, known primarily as an animalier sculptor, combining naturalism with a strong impression of movement (12). He regularly visited zoos in Paris and Antwerp, sculpting the animals directly in front of them. Troubetzkoy shared with Bugatti the love for animals and sculpting style based on vibrancy and movement.

“Whereas the modelling of [Bugatti’s] contemporary Paul Troubetzkoy appeared quick and slick, every mark counted in Bugatti’s brilliantly sculpted pieces. Using plastilene, he pinched, nipped and pressed the material with immense skill” (13).

Echoes of impressionism appear much later in the work of Bourdelle’s student Alberto Giacometti. Giacometti was to explore similar ideas:

“Since I wanted to realise a little of what I saw, I decided, in desperation, to work at home from memory…This resulted, after many efforts which touched on Cubism…in objects which were for me as close as I could get to my vision of reality“14

It could be argued that Troubetzkoy had anticipated Giacometti’s work. Both works are characterized by stretched and light figures, as well as an intensified sharpness of the bronze. Facial details and features, which are still visible in Troubetzkoy’s work, fade in Giacometti’s Femme de Venise VIII.

Sculptural impressionism’s open attitude towards materials, surfaces as well as body shapes and poses marked the remaking of traditional 19th century techniques, and paved the way for future art movements, where geometric forms start taking over.

References

- Alexander Adams Art, “Impressionist Sculpture”, 15th July 2020 https://alexanderadamsart.wordpress.com/tag/paolo-troubetzkoy/Jo Lawson-Tancred, “What did Impressionism mean for sculpture?”, 14th October 2020, https://www.apollo-magazine.com/impressionist-sculpture-staedel-museum-review/

- Trevor Fairbrother, Arts Magazine 6 (February 1987), p. 64-71

- Madeleine Emerald Thiele, “Sargent The Impressionist”, accessed 31st March 2021, https://madeleineemeraldthiele.wordpress.com/2016/07/16/sargent-the-impressionist/amp/

- Tate, “Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose”, accessed 31st March 2021, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/sargent-carnation-lily-lily-rose-n01615

- Shaw: An Autobiography 1898 – 1950, selected from his writings by Stanley Weintraub

- Alexander Adams Art, “Impressionist Sculpture”, 15th July 2020, https://alexanderadamsart.wordpress.com/tag/paolo-troubetzkoy/

- The J. Paul Getty Museum, “The Dancer Statuette by Paolo Troubetzkoy and the Incredible Life of Countess Thamara Swirskaya”, https://www.getty.edu/museum/programs/lectures/desmas_lecture.html

- Alexander Adams Art, “Impressionist Sculpture”, 15th July 2020, https://alexanderadamsart.wordpress.com/tag/paolo-troubetzkoy/

- Svetlana Domogatskaya, “Paolo Troubetzkoy and Russia”, The Tretyakov Gallery Magazin, issue n. 2, 2009, https://www.tretyakovgallerymagazine.com/articles/2-2009-23/paolo-troubetzkoy-and-russia

- Alexander Adams Art, “Impressionist Sculpture”, 15th July 2020, https://alexanderadamsart.wordpress.com/tag/paolo-troubetzkoy/

- Svetlana Domogatskaya, “Paolo Troubetzkoy and Russia”, The Tretyakov Gallery Magazin, issue n. 2, 2009, https://www.tretyakovgallerymagazine.com/articles/2-2009-23/paolo-troubetzkoy-and-russia

- Sladmore Gallery, “Rembrandt Bugatti”, https://sladmore.com/artists/rembrandt-bugatti/#a

- Sladmore Gallery, “Rembrandt Bugatti”, https://sladmore.com/artists/rembrandt-bugatti/#a

- 1901-1966 (Exhibition Catalogue), National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh & Kunsthalle, Vienna, 1996, p. 12.